By Li, Tzu-ning

From the vantage point of Taiwan, Orchid Island appears distant and strange. Although it is only 40 nautical miles from Taiwan, that short span separates two very different worlds–one ever-evolving, modern and dynamic; the other existing peacefully in the past. Summer typhoons are apparently the only things that hit Orchid Island before they hit Taiwan.

The people of Orchid Island call themselves the Tao, but they are known as the Yami, which is the name the Japanese gave them when, as colonizers of Taiwan, they came to Orchid Island in the early 20th century. The efforts of many anthropologists in the intervening years have left us with a general impression of the Tao as a people content with their fate, living on a small island and at peace with the world, in this respect quite unlike the headhunting aborigines of Taiwan. We see them as builders of seaworthy and beautifully ornamented canoes, which they use to catch flying fish. The men usually wear simple loincloths, but on special occasions–such as the Flying Fish Ceremony, celebrations at the completion of new house or boat, or government Functions–they dress up, wear silver helmets and dance. As for relations with authorities of Taiwan, the most notable contribution the ROC has made on Orchid Island since taking over from the Japanese has been to build a nuclear waste storage facility there.

This is the extent of what most Taiwanese know about Orchid Island. While Taiwan has gone through all manners of transformation as it has modernized, our views of the Tao have hardly changed. When we talk about Orchid Island and the Tao, the images that come to mind are still those conveyed by early 20th century Japanese ethnographers and natural historians, such as R. Torii, Ushinosuke Mori and Tadao Kano. We see the well-balanced canoes pulled up on the curving coastline, the richly attired men and women gazing blankly at the camera, the rows of houses with porches of varying heights, the ceremonies that seem to go on and on with participants who never seem to tire. We see the fishing, the boat making, the weaving, and the ceramics. And behind all these sharply drawn images we see a culture that has become frozen in time. Years have gone by. The Japanese have left and the Chinese have come. But an abstract, overall vision of Tao culture has sunk into our consciousness, where it has ossified.

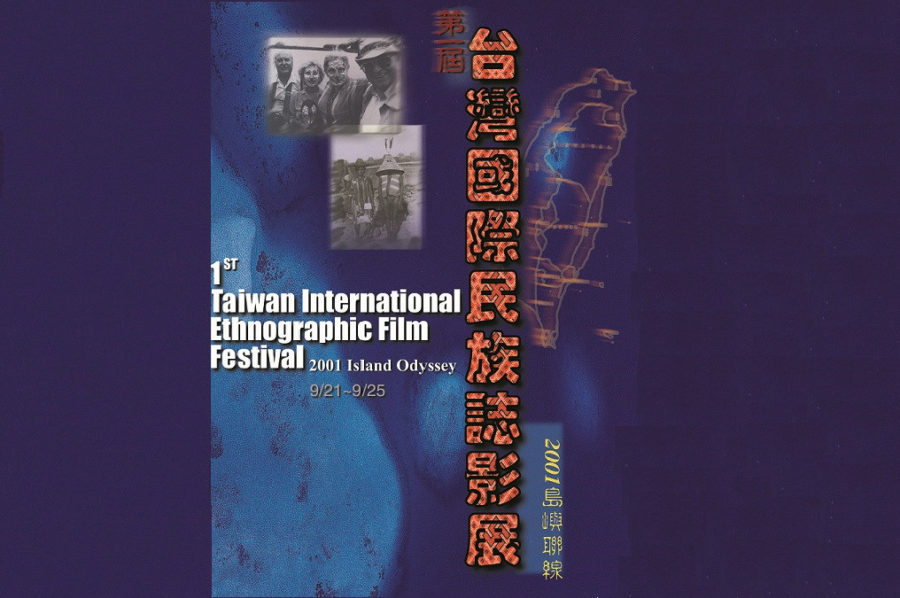

Here at the Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival we plan to present another side of Orchid Island. Of the five films in the “Orchid Island in Focus” section, the earliest was filmed in 1993 and the most recent was filmed in 2000. Part of the great wave of films made about Taiwanese indigenous peoples in the 1990s, these films each have their own style, yet all to some degree challenge the stereotypes about the Tao and preconceptions about Orchid Island, which are rooted in the past. A collective Tao culture is emerging through constant confrontation and dialogue between the modern and the traditional, between “us” and “them,” between the past and the future. With all this mixing and intermingling, an image of Orchid Island is

emerging that is quite different from what we are accustomed to seeing.

Anthropologist Hu Tai-Li’s 1993 film, Voices of Orchid Island, can be described as the first attempt to use film to reflect different points of view about Orchid Island. The Chinese name for the film means “Orchid Island Viewpoints.” Here the word “viewpoints” isn’t referring to traditional ethnography’s all-encompassing viewpoints. This isn’t an example of the “I’m here, so I see; I see, so I know” school. Rather “viewpoints” in this case refers to the three segments of the film, which present three quite different perspectives on Orchid Island. These are then pieced together to form a

whole. The first segment of the film shows a tour group from Taiwan–a jumble of young and old, men and women, with cameras dangling from their necks and hip packs strapped around their waists.

They arrive at the island with the naive of those who have partial understanding and the cruel curiosity of tourists. As they shuttle around the island to catch a glimpse of its “primitive” natural grandeur and tribal life, the scenes they create are inharmonious and full of irony. One is spurred to recall the

thought-provoking line that begins Dennis O’Rourke’s Cannibal Tours: “There is nothing so strange in the strange land as the stranger who comes to visit it.” The second segment of Voices of Orchid Island is about a doctor at a public health clinic, who with great frustration finds himself caught between being viewed as an all powerful in the eyes of the tribal villagers and his own feelings of powerlessness upon confronting the Tao’s deep fear of evil spirits and the ill. The third segment focuses on the political movement against disposing nuclear waste on the island. When a nuclear waste disposal site–such a modern symbol for a threat to life–is placed among people who fear evil spirits, their only recourse and their only way in contemporary political parlance “to stand up for their rights” is to don traditional rattan helmets and pick up their spears and shields.

In comparison to the highly reflective and socially oriented Voices of Orchid Island, Kuo Chen-Ti’s Libangbang: Ching-wen’s not home and Huang Chi-Mao’s Dishes of an Afternoon Meal have the warm and easy feeling of personal essays. Libangbang: Ching-wen’s not home describes how a family passes their days on Orchid Island after their oldest son goes to Taiwan to earn a living. Dishes of an Afternoon Meal, on the other hand, quite simply describes how a family goes about preparing a typical family meal. With this, the camera returns to a favorite anthropological subject: the family, familial relationships and how families make ends meet. These films lack only abstract technical vocabularies and entangling theoretical frameworks. They focus on everyday life–the good and the bad, the joys and the sorrows, the common and the extraordinary. As somewhat lighter fair, these films provide some much-needed relief.

Where Voices of Orchid Island exposed the double terror that results when the traditional belief in evil spirits rubs up against the modern, scientific understanding of illness, And Deliver Us from Evil shows how the Tao can confront and overcome these double fears. It may be difficult for those who aren’t Tao or don’t live on Orchid Island to understand how deeply rooted is the Tao’s fear of the evil spirits they call “anito,” and how this fear extends to avoiding even talking about death, illness or burial rituals. It is harder still to understand what pressure the Tao nurses are under and what courage they show as they confront these spirits despite the opposition of traditional culture, their families and even their patients. This first work by a Tao nurse named Si-Manirei is a moving documentary of what these nurses experience when they go into the villages to care for sick elderly in their homes. In the suffocating crevice between tradition and death, the male doctor in Voice of Orchid Island feels at a loss when confronting evil spirits. The female nurses in And Deliver Us From Evil, on the other hand, choose to tackle them head on.

Tradition can be a heavy burden to face, but at times it has the grandeur of the setting sun. Lin Jian-Hsiang’s Rayon uses the standard methodology of a cultural documentary to convey the meaning and magnificence of catching flying fish in Tao culture. Flying fish are migratory fish and every year in the late spring schools of flying fish visit the waters off Taiwan. Flying fish are the most holy of creatures in Tao mythology, and are also one of their most favored culinary delicacies. The Tao calendar is even divided by the flying fish season. In order to catch these fish, the Tao spend great efforts building canoes and organizing fishing teams, and they observe complicated rules and prohibitions. It could be said that Tao culture almost entirely revolves around the catching of flying fish. Rayon faithfully records this key event in Tao culture.

Thus we return to the Orchid Island of the 1990s, or rather the 1990s “revisionist” interpretations of Orchid Island. Within these we find the weighty magnificence of tradition and the terror caused by a variety of evil spirits, as well as various ways of dealing with that terror. There are the joys and sorrows of every day life, and all the inevitable frustrations. At any rate, as past and present, tradition and modernity, and “us” and “them” engage in confrontation and conversation, we perhaps begin to understand that the distance between Taiwan and Orchid Island isn’t so great after all.

(Translated by Johnathan Barnard)