Tzu-ning LEE

Chairperson, TIEFF Selection Committee / National Taiwan Museum

1.A Rainbow of Color

At the beginning of this year, when we finally decided that “Indigenous Voices” would be the theme for the 2007 Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival, we had no idea from what angle and in what form the theme would be interpreted and presented. The spirit of indigenous voices in this the fourth year of the Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival emphasizes the viewpoint of the “local,” not the “center.” It respects the voices of indigenous peoples and minority groups from around the world and encourages them to exercise their right to speak up. We are no strangers to this theme. In fact, you could say that it has been a recurrent theme throughout the festival’s existence. So we were just a bit concerned that this year’s films wouldn’t do justice to a theme that has remained so important for the festival.

After films were received over the month of June, committee members entered the around-the-clock “film viewing phase” of festival preparation. Films of various themes, forms, and styles came in from all over the world. Some were long, some short, some profound and moving, some sharp and avant-garde. Some would leave you nodding your head in vigorous agreement, while others would leave you scratching your head. The more than 300 films sent in formed a rainbow of diversity so vibrant that we no longer had to worry about whether or not “local” voices would be neglected; rather, we were now concerned about which voices would be heard and which ones wouldn’t.

Due to the objective or technical limitations of the film festival and the subjective biases of the judges, however, we were deeply aware that it would be unavoidable that some wouldn’t be heard. Each film was judged on how closely it adhered to this year’s theme, its technical level, and style. They were also compared with each other. Trimming the list was necessary, but failing to be chosen by no means meant that a film was inferior. Perhaps the one thing that we can be sure of is that following the time-consuming judging process, all the selected films were outstanding in terms of technical style. More importantly, they represented unique, moving interpretations of “indigenous voices”—the festival’s longtime theme.

Nine foreign documentaries were selected as theme films for this year’s film festival. They were from Asia (Thailand, Nepal), the Americas (the US, Canada), Africa (Ghana, Cape Verde), Europe (Croatia), and Oceana (Papua New Guinea). They encompass a wide array of themes, from the lively and sultry music and dance of Africa’s Cape Verde to traditional Kampuchean dancing. Other films include Nepal’s sacred and dangerous version of “Wang Yeh’s Tour of the Land,” female Nepalese dancers who perform a balancing act between the sacred and the worldly, Ghana’s grassroots horror movie industry, a Croatian town’s masquerade festival, the Mlabri, a tribe from Northern Thailand seeking its ethnic identity, the rediscovery of the white man’s culture by the Inuit people of the Arctic, and finally a family burial organized by an anthropologist. In terms of artistic expression, the lineup includes orthodox ethnographic films shot by anthropologists and meta-ethnographic films that have completely overturned and reversed the relationship between researcher and researched, between filmmaker and subject. It consists of faithfully recorded observational films as well as films in which filmmakers actively intervened. Some are humorous and satirical, others moving, and still others solemn. Overall, these diverse films follow no single pattern or style. In terms of depth and breadth of content as well as style and form, they expand the theme and scope of indigenous voices set by the festival.

2.Music and Dance

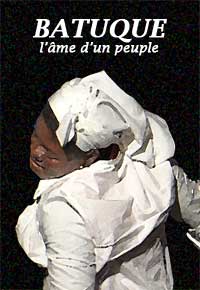

The theme for this year’s festival is indigenous voices and three of the foreign films chosen to be shown are about music and dance. You could say that they interpret “indigenous voices” from the perspective of music and dance. The film Batuque is about a unique type of music called batuque passed down through the generations by the inhabitants of Cape Verde, a group of 15 islands located in the North Atlantic off the western coast of Africa. It was colonized in the 15th century by the Portuguese who transported slaves purchased from all over Africa to the islands. The first residents of these previously uninhabited islands brought with them the seeds of batuque music which is traditionally performed by female dancers and singers. The singers sit around in a circle to croon and keep time by slapping cloth draped across their knees, while the dancers perform their intense provocative hip movements inside the circle. Batuque was strictly banned by the authorities when Cape Verde was under Portuguese rule, but the tradition of batuque music survived and has continued to this day. This film tells the story of Raiz de Tambarina, one of Cape Verde’s oldest batuque dance troupes. Its members are not professional; rather, they are everyday people from all walks of life, making their livings as drivers, fish mongers, saleswomen, what have you. The one thing that ties them together is their passion for batuque. The film takes us deep into their lives and documents their performance, daily lives, and what performing batuque means to them. Through the film’s documentation of the life, history, and music of the islands, we see how this local music, once suppressed and considered indecent by the islands’ colonial rulers, survived the prejudice and prohibition of the colonial period to become the most distinctive symbol of Cape Verde’s contemporary culture.

Batuque shows how the rhythmic, stirring, and sensual dance helped the people of Cape Verde endure colonialism. Seasons of Migration, however, employs the leisurely and stylized traditional court dance of Kampuchea to portray the mindset of modern Kampucheans forced to leave their country. Long Beach, California has the largest population of Kampucheans outside of their homeland. They come from various backgrounds and emigrated from their homeland during different periods and for disparate reasons. Despite these differences, each immigrant has faced similar psychological dilemmas—striving to blend into their new society, but not wanting to cast aside their traditions. In order to overcome this conundrum, they go through a series of stages in which they must adapt mentally to make their new home truly home. After immigrating to Long Beach, Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, who received training in traditional Kampuchean dance as a young girl, continued her studies UCLA. She attempts to express the mental changes that new immigrants undergo using the language of traditional Kampuchean dance. Seasons of Migration documents the four stages of mental change that the new immigrants face through traditional music and dance, interlacing the experiences that they undergo during each period. Unhurried music and stylized body language is used to interpret the bleak mental plight of the new immigrants as they waver between their homeland and chosen home, between modernity and tradition, between East and West. Seasons of Migration suggests that sometimes the old and the new need not be mutually exclusive, being born in the West does not mean that you cannot discover the East, that you don’t have to be “at home” to make your “local voice” heard.

The third film that deals with music and dance comes from the ancient Himalayan kingdom of Nepal. Like many other nations with long traditions, Nepal’s traditional dance and dancers are facing localization and globalization and the choices and pressures they entail. Nepal’s traditional dance and the rites of its Buddhist and Hindu belief systems are intimately related. One could say that Nepal’s dancing is essentially a sacred performance. Faced with the twin torrents of globalism and secularization, the dancers of Nepal, especially the female dancers, find themselves in an awkward position. On the one hand, they are the sacred interpreters of traditional belief, on the other, Nepalese society is often critical of their performances in worldly venues, feeling that they have compromised themselves morally. This film depicts their struggle in their rapidly changing culture and their search for a way out of their predicament. The film’s director, a dancer with a Nepalese/Czech background, brings her camera deep into Kathmandu—Nepal’s capital and largest city—to record the voices of dancers living at its heart. Some are filled with ideals, others simply drift along. This brief sketch of their lives reflects the significance of dance and dancers in today’s Nepal and the transformation both are undergoing.

3.Old Vs. New

Ethnography and ethnographic films traditionally or ideally encourage the viewer to see the world through the eyes of other individuals or ethnic groups. Over the past century, however, the production of ethnography and ethnographic films has continued to primarily follow an established model that emphasizes division of labor—researchers record, subjects are presented and written about. Although they try to stress the spirit of the “native’s point of view,” in reality, it has all but been neglected. Recent years have seen a gradual change in this situation. Once presented and written about, indigenous peoples are now taking up camera and pen to not only record their own stories, but to turn around and record those who once studied them. Sometimes, like their predecessors, they can’t avoid looking through eyes distorted by bias.

Qallunaat! Why White People Are Funny, being shown at the festival, is a sardonic example of this kind of film. It has turned traditional documentary films on their head. “Qallunaat” is the Inuit word for “white man.” Historically, Inuits, who reside in the Arctic Circle, have been one of the ethnic groups most frequently studied, documented, presented, and written about by the “white people” from the south. The topic and main characters of Nanook of the North (1922), a classic by R. Flaherty—regarded as the originator of documentary films—are Inuits, also commonly known as Eskimos. After a century of being the subject of study and documentation, they decided to take up research materials and cameras themselves to study and record what they consider hilarious about the white man’s culture. Such things as rituals they perform when they meet, the way they suppress natural bodily needs, their awkward courtship ritual, the way they complain about being ignored, their irrational attempts to conquer the world, their bureaucracy, their fascination with wealth, and their need to have police officers serve as nannies. Inuits find these bizarre customs and attitudes both hilarious and worth studying, so they established the Qallunaat Study Institute (QSI) to research and document this peculiar ethnic group. The fact that one of its producers is also CEO and the head researcher of QSI increases the academic value of the film. Anybody who finds the white man’s culture funny will want to watch this film over and over again.

Qallunaat! Why White People Are Funny throws the perspective and image production methods of traditional ethnographic films on its head in a spirit of sarcasm and jest. In the same way, The Turcisce Carnival challenges films that limit themselves to observation. Its subject is the masquerade party in Me?imurje, a village in northern Croatia. In the past, the Me?imurje festival was renowned for simple wooden masks, traditional music and musical instruments, and historical skits, but when a director and camera personnel raced to the village to film it, they discovered that the festival hadn’t taken place there for forty years. Each year, performers prefer going elsewhere to perform the masquerade festival rather than stay in Me?imurje. What’s more, the more deeply the filmmakers dug, the more secrets they discovered, like the fact that the town’s two mask makers—one old and one new, are the center of a dispute. The townsfolk are split into two camps, each uncompromisingly supporting one or the other. What’s more, the locals knew that there would be cameras in the town to shoot this year’s festival and this made them want to break with the “tradition” of performing the festival elsewhere and bring it back to Me?imurje to perform it in front of the cameras. The appearance and involvement of the filmmakers and their cameras served to change how the villagers conducted this ancient tradition. This tested the attitude of locals in regard to their traditions and the idea of the objectivity of documentary films and filmmakers.

The makers of The Turcisce Carnival wonder if it is truly possible for the “omniscient,” objective, and invisible camera people in observational filming to really avoid presenting a world untainted by their own biases. Ghanaian Video Tales is a grassroots tradition that stands in sharp contrast to Hollywood’s global moviemaking industry. Hollywood used its copious funds, advanced technology, and powerful marketing capabilities to dominate the world’s movie markets throughout the second half of the 20th century. The world became little more than Hollywood’s cultural colonies, but in the small African nation of Ghana, the term “movies” isn’t tantamount to “Hollywood.” How has this tiny nation been able to resist Hollywood’s “nefarious” cultural empire? The answer: videos. Since the 1990s, affordable videotapes became commonly available and began to change Africa’s media world. The unique new genre of Ghana’s horror films arose against this background. The popular Snake Man series depicts the snake man transforming women into money-making prostitutes. Despite the bizarre/absurd plots and the primitive shooting and acting, the films seem to strike a chord with the locals. What’s more, with the widespread ownership of video recorders and affordable, easy-to-handle tapes, movies can be hawked on the street. Driven by local tastes and marketing methods, the Snake Man series became an overnight success and laid the way for Ghana’s new and highly popular local horror films. Ghanaian Video Tales documents the rise of this unique genre, including what happens in front of and behind the scenes of Ghana’s local horror films, and the reactions and reflections of actors and directors. In the face of the global barrage of Hollywood movies, Ghana’s locally-made horror films have done exceedingly well and won over the hearts of local viewers.

4.Identity, Religion, and Family

Is there still room for local voices to be heard in the face of globalization? As ways of life, economic lives, religious beliefs, and ideas in general from different areas around the globe integrate at an alarming pace, do local differences mean anything anymore? In recent years, debates have revealed that the desire to belong is another facet of globalization. Despite the trend toward globalization, therefore, geographical boundaries have remained in a state of flux, while, insistence on some kind of demarcation line has continued to be a key characteristic of our current age. Phenomena of this sort have seen increasing resistance between minority groups and outsiders (anthropologists, tourists, etc.) as they fear that their cultural knowledge, identity, and economic resources will disappear as a result.

The Importance of Being Mlabri focuses on searching to belong in a rapidly changing world. In the past, the Mlabrim, an ethnic group that inhabited the jungles of Northern Thailand, survived by hunting and gathering. In recent years, however, the expanding agricultural and logging industries have caused their forests to shrink. Unable to maintain their old way of life, the Mlabri people have been forced to relocate to nearby villages where they do odd jobs or agricultural work for other ethnic groups. But to their minds, their hard life is of secondary importance. What truly concerns the Mlabri is whether or not their traditional culture and the identity that their people have with that culture will continue to exist as they serve outsiders (i.e., Thais and other ethnic groups of the mountains). Their traditional way of life is gone for good, but how can they adapt to their new surroundings without losing their traditions? With a current population of only 320, the Mlabri face this precarious situation and threat on a daily basis. We watch as a group of Mlabri children prepares to go study at a Thai boarding school. The children look excited, but the parents are frightened that they will be assimilated by outsiders. Unable to find any unbetrothed Mlabri girls, young men are forced to seek mates outside of the village where they find themselves in a sea of other ethnic groups. This is a story about how one group of people searches for identity in a changing world. You won’t see main characters shouting until they’re blue in the face about all the wrongs visited upon them. This film focuses rather on touching images and the equally touching sound of the Mlabri tongue to show the tenacity of the Mlabri and their determination not to give in.

Faced with life’s vicissitudes, some people simply bow their heads in acceptance and many turn to religion. On The Road With the Red God: Machhendranath depicts a splendid religious rite performed every 12 years in Nepal. It differs from many other religious ceremonies in that it is “mobile.” Tens of thousands of believers cluster around a tower 19 meters in height set atop a huge wobbly wooden cart. They tour the country on rugged narrow mountain paths for over a month. In addition to zealous veneration of the “touring god” Machhendranath and various rites and sacrifices performed prior to the tour, the biggest test is the actual handling of this wooden cart of Trojan horse dimensions as it proceeds while surrounded by thousands of enthusiastic followers. Believers are all aware of the dangers involved in this sacred journey. The mammoth vehicle, made out of traditional materials using traditional tools, could topple over at anytime—it wouldn’t be the first time. Many people remain traumatized from the last unfortunate episode and the ensuing disaster. This year, as the “Mighty Miracle God” prepares to hit the road again, believers’ hearts are filled with both apprehension and anticipation and the entire nation is holding its breath and watching attentively. According to tradition, this mighty red god evaded pursuing evil spirits to bring blessings to our world. Will he be able to elude them again as they lie in wait for him this year? Will his tour of the land proceed free of hitches? Perhaps it depends upon everyone’s faith.

The success or failure of a religious ritual can impact the emotions of thousands of followers. In the same way, the appropriate handling of a funeral can influence family relations. This is the theme of the film Ngat is Dead: Studying Mortuary Traditions. Danish anthropologist Ton Otto’s godfather passed away. They met when Otto was performing field studies on the Melanesian island of Baluan. Local tradition dictated that he hold a funeral for his dead father, but upon his return from Denmark, he found that a funeral had already been held by another son. Driven by his promise to his godfather and his understanding of island tradition, he decided to hold a second funeral. His decision triggered both positive and negative reactions from relatives. The ceremony finally took place amidst a cloud of contention as both sides cited tradition to support their cases. The controversy continued to spread. Some family members were very pleased; others felt they were treated shabbily. The happy ones praised the success of the ceremony; the unhappy ones went to great pains to show complicated genealogy charts and how they had been slighted. The funeral showed that family relations are not simply some abstract idea—a genealogical chart in an anthropologist’s notebook. It illustrated rather that they are something to be haggled over. Each person felt that they didn’t receive enough and pointed out jealously that others received too much. This social drama between an anthropologist and locals reveals that the concept of “familial relations” isn’t necessarily as abstract and simple as textbooks would have us believe.

5.Them and Us

Nine films, nine local stories. There is no need to force a common theme or profound meaning. If there is, it is the riveting local story that each film tells and the fact that these films have come together to form yet another exciting ethnographic film festival.

The “what” of the stories is obviously important, but how the stories are told is equally important. Just like good ethnography, quality ethnographic films enable us to feel unique cultural experiences as if we were there; they enable us to bridge cultural and geographic gaps. We sigh and praise them as they take our emotions on a rollercoaster ride as the ethnic groups in the films show us things we’ve never seen before.

Perhaps that is the nature of ethnographic films. Maybe this is the unique allure of anthropology. The different stories of the festival’s various films tug at the similarities in our hearts. Watching stories about others teaches us more about ourselves.

Prior to viewing these films, had you ever seen or heard the singing and dancing of Africa’s Cape Verde, Kampuchea’s traditional dance, Nepal’s Machhendranath’s Tour of the Land ceremony, Ghana’s horror films, or Croatia’s masquerade festival? And who knew anything about the crisis of identity of Northern Thailand’s Mlabri people, the Inuit’s study of whites, the family funerals of the people of Papua New Guinea, and the status of women dancers in Nepal? Perhaps you knew nothing about these, but as Taiwanese, we have seen, we have heard, and we understand Cloud Gate, the Nanguan Puppet Theater, Wang Yeh’s Tour of the Land, the veneration of Matsu, Steven Chow movies, blasting Han Dan Ye with firecrackers to dispel evil, the movement among indigenous peoples to use their traditional names, and the dispute raging in Wang Yung-ching’s family. No concrete relationship exists between the two, but it’s hard to deny that there is a certain level of similarity between them. So just how big or small is the gap between things with which we are familiar and those with which we are not, between what is similar to us and that which is different from us, and between “them” and “us?”