MA Tung-Yu,

Graduate student, Graduate School of Anthropology, National Ching Hwa University

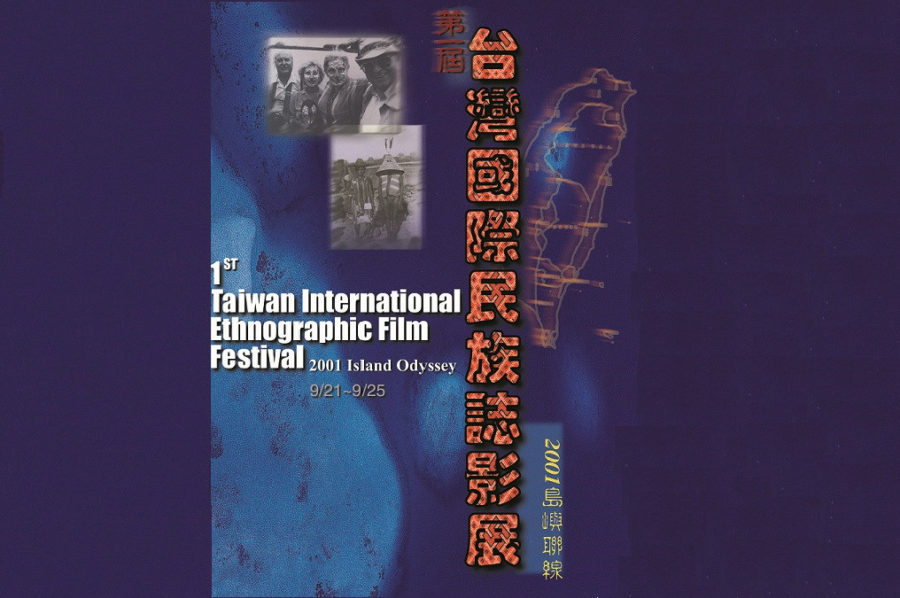

In September 2001, Taiwan will host its first International Ethnographic Film Festival. As a special treat for Taiwan’s audience and connoisseurs of ethnographic films, festival organizers will show three films by distinguished American anthropologist and filmmaker, Margaret Mead, and her husband Gregory Bateson: Trance and Dance in Bali (1952), Kaba’s First Year (1952), and Childhood Rivalry in Bali and New Guinea (1952). These three films will be shown as a special tribute to the two pioneers of ethnographic films.

British anthropologist Nigel Barley once said that all anthropologists believe in the idea that hidden in every culture within all races are different secrets which make up parts of a whole truth regarding the entire human race; and that it is the responsibility of anthropologists to uncover this truth. The ways by which their findings would be presented is through the keeping of ethnographic journals and records. With the passing of time however, different attitudes and opinions would set ultimately different trends in the styles and modes of ethnological representation. In the early days of anthropological study, scientific interest and its predisposition for providing clear evidence dictated the mode of keeping ethnographic records. Emphasis was put on objectivity and logical reasoning for all of the information and testimonies submitted. Later day anthropological studies show a growing inclination toward a humanitarian mode of representation as a result of the influences and development of symbolic and interpretative anthropology. This new mode of representation can be seen in the writings of American anthropologist, Clifford Geertz.

If the shift from scientific to humanitarian focus is true in ethnographic literature, it is probably more evident in ethnographic films. With documentaries made in recent times, audience can often easily feel and experience the filmmakers’ own powerful emotions and personal motives in their films. Albeit non-fiction, the documentary nature of ethnographic films often mix the emotions and dispositions of the filmmakers together with the subjects of their films; thereby making the projects whole in an absolute way. Early ethnographic films present an altogether different appearance with that of recent ethnographic films: often, the incident or subject in focus would be sterilized and all related actions or developments portrayed would promise objectivity. For the filmmakers of these early ethnographic films, the most important goal of these video journals is to testify for or against an assumption or theoretical development; and not to be used as a transmitter of personal emotions or opinions. So when an audience sits through an ethnographic film, it may in fact be difficult for them to fully grasp the authors’ motives and styles without first having some ideas of their creative background.

The same kind of preparation is in fact required for the audience to appreciate Mead’s work. To fully comprehend the spirit of the three Margaret Mead films on exhibition here, it is necessary to take a look at her anthropological background.

Margaret Mead was born in 1901. In the early 1920s, she became a student of the most prominent anthropologist in the US at the time, Franz Boas (1858-1942). Mead was completing her Master’s Degree in Psychology before she met Boas, but later decided to switch faculties and went on eventually to pursue a Doctorate Degree in Anthropology.

Boas was born in Germany and taught at the University of Berlin before he became naturalized as an American citizen. In 1899, he became a Professor at Columbia University. Anyone who has delved into the development and history of anthropology will know the extent to which Boas influenced early American anthropology. He had a great number of students, many of whom became outstanding anthropologists themselves, making crucial contributions to the development of American anthropology.

At the time, the scientific world was obsessing over Darwin’s revolutionary theory affecting the entire human race. In his book The Origin of Species published in the 1860s, Charles Darwin expounded his theory of evolution. In the beginning of the twentieth century, the tremendous faith in the theory of evolution postulated that everything from the notion of biological evolution, to the formation and variations of human nature, are an expression and result of heredity and evolution.

Anthropologists like Franz Boas however, were highly opposed to the evolutionist interpretation of human nature. For Boas, the reasonable explanation is that the environment and social conditions are the primary concern and influence in the evaluation of individual capabilities. Boas claims that the variations in human nature are the result of different cultural restrictions instead of the influence of hereditary biology. The absolute conviction of cultural influence in the explanation of human behavior and nature; the rejection of biological, ethnical, and environmental elements, have given anthropologists like Boas and his followers, the label of cultural determinists.

Under the guidance and influence of Franz Boas, young Margaret Mead also became a cultural determinist. At the age of 24, she went alone to the Samoa Islands in the South Pacific to study adolescent response at Boas’ request and instruction. The basis of this study assumes that if the rebellious nature of American adolescents is the result of biology, then Samoan youths should display the same rebellious attitude. Likewise, if American adolescent rebelliousness is the result of cultural restrictions, then Samoan adolescents should display an array of different response due to the different cultural background. In nearly a year of field research, Mead completed her book Coming of Age in Samoa (1928). For Boas and his supporters, Mead’s book symbolized the total triumph of cultural determinism over the theory of evolution on biology and heredity, in the formation of human nature.

Decades later however, a number of new generation anthropologists, in particular Australian anthropologist, Derek Freeman, raised severe criticisms on Mead’s book. Freeman conducted 6 investigations in Samoa over forty years. The result of his investigation claimed that Mead’s Book, Coming of Age in Samoa was simultaneously the construction and destruction of an anthropological myth. As the author of this essay, I do not intend here to challenge the academic value of cultural determinism, nor to instigate a critical discussion of Mead’s field research technique. It is however, necessary to point out the impact of Boas’ influence and theory of cultural determinism, as it would directly shape Mead’s theoretical inclination as well as her cinematic style.

As Karl G. Heider points out in his book Ethnographic Film, Mead’s films confirms her own beliefs and theories. In the 1930s, she worked in Bali and New Guinea for a significant amount of time. The three films on exhibition at this festival were shot then, but with final edits completed in 1952. In spite of this, we can still see Mead’s determination and disposition, from the final product through the editing and narration. Particularly with Kaba’s First Years and Childhood Rivalry in Bali and New Guinea, audience can see that the focus of these two films lies in the influence of different cultural environment and child-rearing methods, on the children’s personalities. To put it bluntly, the integral conscience of Mead’s films is still cultural determinism.

To ensure scientific objectivity, Gregory Bateson explains that the camera used in these field researches was merely a tool for recording data. Mead’s husband, Gregory Bateson worked as the cinematographer on all three films. From Bateson’s point of view, one notices a strong sense of estrangement when watching these three films. The subjects of the camera, as well as the stories being told come across as scientific specimens only. And during editing in post-production, Mead’s narration which repeatedly reminded the audience to ‘look’ and ‘observe carefully’, goes to emphasize the theory to which the film is suppose to prove. Like a teacher instructing her students to look carefully through the microscope, Mead’s narration exposes her attempt to use her films as a tool to prove her belief and theory in the notion of cultural determinism.

In the pioneering of ethnographic films, Mead ’s achievement was fast and conclusive. In the field of visual anthropology, Mead is regarded as an activist as well as a frontrunner. She has spent her entire life trying to promote and encourage the use of visual tools to conduct ethnographic research and investigation; so that we may pass on more and more cultural data to our fellow human being. Half a century has passed by, but on this particular matter, the anthropological society has remained cool and oblivious. For many anthropologists, it is still considered more proper to conduct anthropological studies with words and texts. Visual anthropology is considered nothing but a supportive tool, or sideshow to attract an audience. But one should not forget that it is precisely through these ‘sideshows’ that people have been brought closer than ever to the different cultures via mass media and all its audio-visual gadgets. Furthermore, it has effectively helped people to better understand and imagine the different cultures throughout the world; as well as attract the curiosity of young people so that they may develop an interest and maybe passion for anthropology.

Anthropology is a lonely science. Anthropologists go alone to places far away from home to conduct field research in some distant land. They have to endure all kinds of setbacks, pressure and loneliness. By the time they return home, with a completed ethnographic report, they may be disappointed to find such minimal solidarity and understanding in the world. Just as Claude Levi-Strauss described in his book The Savage Mind: the Paris he met with after coming back from his field research in Brazil was cold and unaffectionate. From this angle, one can say that Mead was given special attention by a higher force. She married 3 times in her life. She met her last two husbands on her researches out in the fields. Both men were anthropologists too, and completed a number of important investigations with her in New Guinea. In particular, had it not been for Mead’s third husband, Gregory Bateson, and his contribution as cameraman, we would not see the birth of these ethnographic films. At the first Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival, we are honored and privileged to have in exhibition, the ethnographic films of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. Although the subjects are plain and simple, they are richly endowed with a sense of historical spirit and soul. We salute the filmmakers and eagerly share in their achievements.

(translated by Jessica, I-Wen Wang)