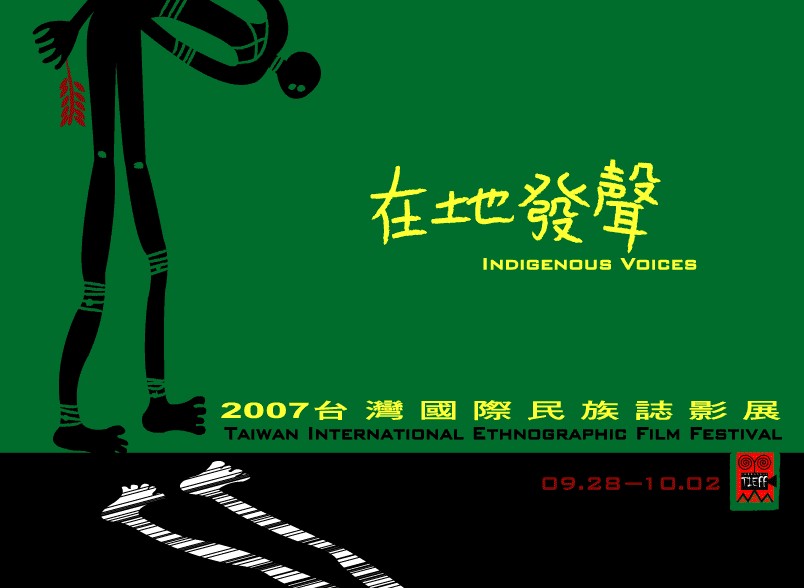

In line with this year’s theme, Indigenous Voices, the 2007 Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival chose to include Native American director Victor Masayesva’s films “Imagining Indians” (1992) and “Water Land Life-H2opi Run to Mexico” (2007).

Victor Masayesva is an extremely relevant contemporary American Indian filmmaker who is a member of the Hopi tribe. With the support of scholarships, he was able to attend Horace Mann High School in New York and Princeton University. After graduation, he returned to his home on the Hopi Indian Reservation in northern Arizona. Beginning in 1980, Victor Masayesva began to photograph and film, using this environment and Hopi Indian culture as a backdrop. He has completed 16 films and documentaries about the Hopi Indians, becoming a kind of spokesman for the tribe.

Victor Masayesva insists on using an Indian subjective viewpoint in his works in order to change mainstream American society’s stereotypical impression of the country’s native peoples. Through the art of filmmaking, he tries to create a platform for the Hopi’s own voices and viewpoints in the hope of shattering the stereotypes of Native Americans portrayed in Hollywood’s film industry. His works reveal the complex emotions and viewpoints of his people, expressing subjective voices, striving for recognition and self respect, and articulating their indignation towards the history of settlement and oppression. To understand Victor Masayesva’s films and the works by other Indian filmmakers, you must first understand both the history of the settlement of the Americas and the USA, plus the area’s contemporary circumstances.

Prior to the American continent’s discovery in the 15th century by Europeans, there was no collective noun to describe this area’s native peoples. In 1492, the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus was seeking a new route to the Indies by traveling west. He instead discovered America, but mistakenly thought he had reached his intended destination. Therefore, he called the people living there Indios. Although he was mistaken, the name stuck and the people in that area were referred to as Indians, which became the collective name of the American continent’s indigenous peoples.

Over the past 500 years, the plight of the Indians facing European colonization (including by the Spanish, Dutch, and English) has been tragic. Beginning in the 16th century, due to European interests in the area, North American Indian people were massacred in battles and conflicts and nearly died out. After American independence, the Indians once again faced a more difficult predicament, the passing of the Removal Bill in 1830. In order to protect the interests of the white people in America, all Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi who had not been wiped out in earlier battles were moved to Oklahoma. The Indian people were shackled and bound together in a line, prodded along by the military as they marched to their destination. The Indian people in America were once again massacred in 1860, leaving only 340,000 in the country. In 1910 the number dropped to 220,000, but then began to rise over the rest of the century, to 550,000 in 1960, 1.43 million in 1980, 2 million in 1990. In 2000, the Indian population reached 3 million. Today, there are more than 200 Indian Reservations, most of which were created after the war. This is one of America’s darkest chapters in its history.

In order to illustrate the basic spirit of rule-of-law of the nation after its founding in the 18th century, the US government signed a treaty with those Indian tribes who had surrendered or swore allegiance to America. The treaty affirmed that the government would grant the Indians living on reservations autonomy and provide all the land they needed to survive. In 1871, the US Congress resolved not to sign or recognize any additional agreements granting autonomy to Indian tribes, but existing treaties remained valid. After the wars with the Indian people ended, the white government pursued a “Peace Policy” in its dealing with the Indians, sending Christian missionaries to rule over them and carrying out an assimilation policy. In 1924, Congress passed the Snyder Act in gratitude for the Indian participation in the First World War. The act gave American citizenship to the Indian people living within the country. The 1934 Indian Reorganization Act authorized Indian people to write their own constitution, elect an assembly, recover their culture, and worship as they chose. The government’s assimilation policy had not completely succeeded.

The deplorable situation that faced Indian inhabitants of America and the ignoble history of white settlement, however, are rarely discussed and sometimes outright ignored. In the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian Institution, the history of the country’s settlement is not one of the featured topics. From the origins of photography in the 1840’s to the 20th century’s film industry, Indians are one of the most popular subjects of entertainment in America. In commercial films, the tragic history of white people’s treatment and massacre of Indians is smoothed over or ignored. Instead, Indian people and culture have been taken up in the mainstream culture’s collective imagination. Indians are seen by whites as the vanishing race, so they are often a subject of recordings and the focus of many a camera lens. If the cameraman does not capture their images on film, the group will disappear forever. To members of Europe’s relatively advanced civilization, the Indian’s primitive civilization was a living specimen, the past that societies like theirs had lost. Indians were noble savages, innocent and pure. In Christian culture, however, Indians were seen as cannibals who enjoyed scalping whites, people of the New World who had been forsaken by God.

It is probably very difficult for Americans to imagine Hollywood films without Indians. Audiences would lose out on quite a bit of entertainment. Without the Indian, we would not have John Wayne in “The Searchers” and we would be without hundreds of other heroes in similar westerns. Kevin Costner could not dance with wolves without Indians, nor could Brad Pitt appear in “Legends of the Fall”. The existence of Indians provided mainstream white society with an essential image and supporting character in its construction of the creed and romanticism of the western hero. Savage Indians are sacrificed to the Wild West hero’s six shooter. Indian princesses may be beautiful, but they always fall in love with the white military officer. The Indian soldier galloping on his horse is always closely followed by brave American cavalry. The Indian land is a lost paradise and there are always white explorers who like to live in teepees and are forever sentimentally attached to the tribe. These stories make up the idea of the imagined Indian in mainstream American society and around the world.

No other indigenous people on Earth are like American Indians. They are a Hollywood movie staple, appearing in a wide range of films and becoming an image in the world’s collective imagination. However, most of the Indians portrayed on film play a supporting role, only appearing to let out a whoop as they ride by on their horses and get shot by our hero. Although there are many scenes featuring Indian people, their characters are often silent, serving as a mere prop. Indian people, as they most commonly appear in westerns, should actually be called invisible people.

Indians did rebel against this image exploitation by mainstream society, but because the whites were always in a position of power, their efforts had little effect. In the past, Indian people have resisted when they were forced to perform their sacred ceremonies in front of the camera. For example, in 1904, when Edward Sheriff Curtis was shooting the Arizona Navajo Indian Yabichi ceremony, the masked participants danced with their backs facing the camera, refusing to be filmed. In other similar incidents, Indians often protested by throwing sand and rocks at the camera, destroying the film, or breaking the equipment. After the Red Power movement of the 1970’s, Indians became more conscious of their cultural rights. Attendees of many ceremonial activities were forbidden to make any type of recording.

Victor Masayesva and other Indian filmmakers, on the other hand, choose to actively utilize their own films to counteract Hollywood films, conveying Indigenous voices to fight the mythologized Indian image. Victor Masayesva once said that his most important objective in producing films is to break through the silence of Indians in mainstream American movies. He often chooses reels of film themselves as his medium, using Hollywood’s own films to combat the Indian images portrayed in the industry’s movies.

Victor Masayesva’s other mission is to convey the voices of his fellow Indians. He believes that still and video cameras are important tools that can preserve and pass down culture. Compared with writing, visual representations offer a more effective communication medium within Indian societies. Besides oral histories, the majority of Indian communication, including ritual activities and historical reenactments, occurs visually.

Images stand alone, while words can convey the thread of a story. Therefore, the integration of images with words or interviews has become a characteristic of Victor Masayesva’s photographs and films. This year’s festival features two of his films, both of which revolve around interviews and the statements of the interviewees, creating the axis upon which the story is built.

In his film, “Imagining Indians”(1992), Victor Masayesva opens with a reedited clip from an old Hollywood western. He uses the interviewee’s words to criticize the mainstream Indian images in the film, probe the representation of power and culture in Indian movies, and express Indians’ long repressed unhappiness at being just a prop in Hollywood films and their anger at how Hollywood distorts Indian culture. As the interviewee, Charles Hustito, says in the film, “White people took our land and restricted us to reservations. Now they are invading our lives and using them to make money. This is completely unforgivable. Respect our religion. We never tried to turn white people into Indians, so just let us be.” In the last scene of the film, an Indian woman lying in a dentist chair gets up and pushes away her chattering dentist who complacently believes that he is a friend to Indians. She grabs his drill and turns it on the camera lens and then pushes over the camera. This striking image of violence to the camera being used to combat the violence of the camera and the technique used to represent this idea merits further reflection.

Water Land Life-H2opi Run to Mexico (2007) is Victor Masayesva most recent work. The film is built around the Hopi Indians’ international long distance run to bring attention to water issues. It uses images of the run and interviews of those involved to explore Hopi attitudes towards the environment.

Hopi is an abbreviation of Hopi’sinom, which means “People Who Live in The Right Way” or “People of Peace”. The Hopi people’s most basic belief is that they must respect other people and all things upon the Earth. People must live their lives according to the instructions of Maasaw (the creator). The purpose of religious ceremonies is to increase the happiness and welfare of the entire world.

According to oral histories, the Hopi are among the oldest of the North American Indian tribes. Currently, the Hopi Indian Reservation is located in the northeastern part of Arizona, surrounded on four sides by the Navajo Indian Reservation. The Grand Canyon National Park lies close to the southwest. Not counting the Colorado River Valley, Hopi land measures tens of thousands of square miles. The area is entirely desert, covered with red sand and enormous rock formations that would be familiar to anyone who has watched a western.

Water is this area”s most valued natural resource. In recent years, I have traveled there to perform fieldwork. I was hosted in the home of some Navajo Indians located in the middle of the desert, so remote that there was no running water or electricity. Each week, the family must drive their truck to purchase water. They had to walk over six hours back and forth each day to lead their sheep, the household’s only assets, to a small reservoir. It rains fewer than twenty days out of the year and the number goes down even further during droughts. Such difficulties are almost unimaginable for those who have not experienced lack of water on this scale.

Groundwater is an important source of water, but the land is also rich in coal, gold, and turquoise. Mines extract large amounts of groundwater to wash the ore and process the excavated materials. After use in the mine, the waste water is dumped out, polluting the groundwater. Rational use of the area’s limited water resources is essential to the survival of the area’s Indian peoples.

Rather than resorting to violent protests, the peace-loving Hopi Indians decided to use this long distance run to bring attention to the issue among tribe members and the outside world. Carrying maize to represent life and other ceremonial objects such as branches and ladles, a group of Hopi people started the 2000 mile run south to Mexico. Along the route, they stopped to pray and chant with different groups and organizations that they met. The Hopi shared their message that water is the source of all life and by treasuring water, we can begin to respect others and seek world peace. For those living on Taiwan, which is buffeted each year by flood-inducing typhoons, the Hopi’s reverence and respect for water leaves a very deep impression.

Ethnographic and documentary filmmakers around the world often come in conflict with those they film on moral principles. The majority of filmmakers still respect indigenous voices and native points of view, hoping that through sharing their films they can achieve cross cultural understanding and tolerance. The eternal questions are, “How can we make people understand another culture? Is that even possible?” I believe that it is not only an indigenous person who can understand and express an indigenous voice. However, filmmaking requires technical knowledge and a large capital investment, so often it is an outsider who provides the means for an indigenous person to express his own indigenous voice. This is especially the case when the indigenous people belong to a politically or economically disadvantaged group. After watching many ethnographic and documentary films made by outsiders, Victor Masayesva possibly hoped, as an Indian himself, to give the audience another perspective on indigenous voices and a native point of view. We aim to present viewers with this kind of contrast, the most interesting and introspective experience we can provide at this year’s festival.